Cross Keys

8 June 1862

The

The 74th’s first battle was that of Cross Keys. In the early Summer of 1862, the Union Army was

hoping to capture Con. Gen. Stonewall Jackson in the

The valley floor is undulating hills with high steep mountains

that gradually rise from the valley and then steepened towards the summit. With the forested hills, they were impassable

by large scale forces, and difficult to cross over by just a few

individuals. The valley was served by a

main road that was predominately used by wagon’s – the river being the

predominate feature. The valley was

vital to the Confederacy – it was the “breadbasket” of

In late May, at Front Royal,

On the 8th of June 1862, the small

At 8:30 a.m., Cluseret’s Brigade came into contact with the

Confederate Army of Gen. Jackson. What

Cluseret didn’t know at the start was that the 15th

Bohlen’s

Brigade (74th and 75th PA, 54th and 58th

NY,

Bohlen’s

Brigade (74th and 75th PA, 54th and 58th

NY,

As the men came into position as the far left of the Union line,

the heat in the middle was getting more intense as the Confederate forces began

pushing on Stahel’s wounded  brigade. Bohlen’s forces took positions on a

relatively rolling piece of ground in and about the Ever’s Farm.

brigade. Bohlen’s forces took positions on a

relatively rolling piece of ground in and about the Ever’s Farm.

The rolling terrain is such that even today, one can quickly see

how regiments were not easily seen.

Trees were more common in the region than today and the small creeks

that cut through the landscape provided cover for moving troops. At 2:30 p.m., the Colonel Hamm’s men were

formed into a line of battle by Gen. Bohlen.

As that took place, General Blenker decided to take a very acute

interest in the manner in which the brigade and the regiments therein were to

proceed. Rather than focusing on the

overall strategy of his division, Blenker at about 2:40 p.m. detailed companies

A & G to act as skirmishers without reserves and then specifically ordered

the men to protect the wounded of the 8th NY that were believed by

Blenker to be coming towards this part of the line.

From the

position near this turkey breeding farm, the regiments moved towards the left

of the photograph. The 8th NY

was in about the center of the picture where woods can still be found

today. As the regiment began to slowly

advance behind it’s skirmishers, the 13th

From the

position near this turkey breeding farm, the regiments moved towards the left

of the photograph. The 8th NY

was in about the center of the picture where woods can still be found

today. As the regiment began to slowly

advance behind it’s skirmishers, the 13th

Still proceeding cautiously, and following the order not to fire

at men in front of them with the expectation that any such men would be the

wounded of the 8th NY, the skirmishers advanced through the wheat

field.

The wheat field would have been in this lowed area – still used

for such crops  today. The farmer informed us that the ground isn’t

the greatest for crops due to the amount of rock in it. The skirmishers would have advanced from the

today. The farmer informed us that the ground isn’t

the greatest for crops due to the amount of rock in it. The skirmishers would have advanced from the  gracious,

as well as pleased that we stopped to ask him if we could walk on his

property. PLEASE DO NOT GO ON PRIVATE

PROPERTY WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE OWNER.

gracious,

as well as pleased that we stopped to ask him if we could walk on his

property. PLEASE DO NOT GO ON PRIVATE

PROPERTY WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE OWNER.

Lt. Brandenstein, an aide of Blenker’s, accompanied the

skirmishers and when the skirmishers encountered forces in front of them – they

were told to cease their fire. The

presumption being the men in front of them were the wounded of the 8th

NY. However, that error would prove the  undoing of

Lt. Brandenstein. A series of quick and

deadly volleys came from the edge of the wheat field where a fence was catching

the skirmishers and Brandenstein. The

Union skirmishers returned fire and followed the Confederate skirmishers back

into the woods at a position approximately left of the trees in this picture on

the left side of the

undoing of

Lt. Brandenstein. A series of quick and

deadly volleys came from the edge of the wheat field where a fence was catching

the skirmishers and Brandenstein. The

Union skirmishers returned fire and followed the Confederate skirmishers back

into the woods at a position approximately left of the trees in this picture on

the left side of the  fence.

fence.

At a point of some sixty feet (20 paces), the 74th

skirmishers found themselves starring into the face of the Confederate

regiments attempting to flank this part of the Union line. Major Blessing ordered the men to fall back

to their  left –

towards the present day road. The ground

rises out of this small hollow as one can see in these pictures. The men had retreated about sixty feet to

another fence while receiving “torrents of musket-balls.” Bret and I suspect that this second fence

could be in the location of the fence seen in these three pictures…the initial

fence possibly being on the other side of the small creek that is barely

visable to the left of the fence (above and to the left). Seeing the predicament of the 74th,

the 75th sent forward companies to assist as Captain Wiedrich’s

three pieces began to load canister.

left –

towards the present day road. The ground

rises out of this small hollow as one can see in these pictures. The men had retreated about sixty feet to

another fence while receiving “torrents of musket-balls.” Bret and I suspect that this second fence

could be in the location of the fence seen in these three pictures…the initial

fence possibly being on the other side of the small creek that is barely

visable to the left of the fence (above and to the left). Seeing the predicament of the 74th,

the 75th sent forward companies to assist as Captain Wiedrich’s

three pieces began to load canister.

By this point,

While holding their position, the

The 74th didn’t participate in

Bret here is

contemplating the place where the initial exchange of skirmishers occurred on

that June day. There is little in the

way of development or significant change to this part of the battle field.

Bret here is

contemplating the place where the initial exchange of skirmishers occurred on

that June day. There is little in the

way of development or significant change to this part of the battle field.

The right

side of the

The right

side of the

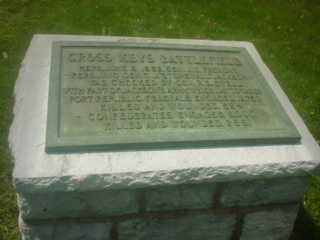

Here are

the examples of the signage that has been put in place for the benefit of

travelers. The work to preserve the

battlefield is discussed at

this website and at

this one. The Shenandoah Valley

Battle Fields foundation has worked in various ways with land owners to

preserve what is relatively undeveloped land.

Here are

the examples of the signage that has been put in place for the benefit of

travelers. The work to preserve the

battlefield is discussed at

this website and at

this one. The Shenandoah Valley

Battle Fields foundation has worked in various ways with land owners to

preserve what is relatively undeveloped land.

Any one

planning a trip to the battlefield should spend time studying the Shenandoah At War website. Packed with a lot of great information, this

site truly is an example of how history, conservation, and tourism promotion can

be brought together in a truly remarkable and professional manner.

Any one

planning a trip to the battlefield should spend time studying the Shenandoah At War website. Packed with a lot of great information, this

site truly is an example of how history, conservation, and tourism promotion can

be brought together in a truly remarkable and professional manner.

Also worth having if you plan to visit is the map packet created

by Mark Collier for

the Battle of Cross Keys. Through

the use of a printed Mylar slide and three topographical maps printed with

troop positions, this map set is a great bargain for less than $10. The packet includes a brief description of

the battle, an order of battle, and most importantly THE MAPS. Highly recommend this map set to anyone.

Also, be sure to read through Lt. Col. Hamm’s report on the battle

and have a copy of it with you if you visit.

Again, don’t walk on private property without permission of the

owners.

Bibliography

![]() Battle of Cross Keys

– Mark C. Collier, 1996.

Battle of Cross Keys

– Mark C. Collier, 1996.

![]() Battlefield –

Peter Svenson, Faber & Faber,

Battlefield –

Peter Svenson, Faber & Faber,

![]() The Battles of Cross Keys and

The Battles of Cross Keys and

![]() The Valley of

the Shadow - John D

Imboden, "Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah," Battles and

Leaders of the Civil War, Volume II, pages 282-298.

The Valley of

the Shadow - John D

Imboden, "Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah," Battles and

Leaders of the Civil War, Volume II, pages 282-298.

![]() Research notes of Bret Coulson,

Research notes of Bret Coulson,